Charter schools, as public schools, are funded at taxpayer expense – mostly in the form of tuition payments from school districts. Explore the questions below to learn more about how charter school funding is unfair and results in significant negative impacts on school district and state budgets.

No.

While it is true that the families of children who attend charter schools do not pay any tuition directly to the charter school, students attend charter schools at public expense. School districts are required by law to make a tuition payment to a charter school for every student residing in the school district who enrolls in the charter school. This includes students who enroll in a charter school and were previously home-schooled or attended a nonpublic school, even if the students were never enrolled in the school district.

In 2021-22, total charter school tuition payments (cyber and brick-and-mortar) were more than $2.6 billion. To put that into perspective, that would pay the average salary of nearly 36,800 teachers and is 3.8 times what school districts spent on providing students with career and technical education programs. More than $1 billion of that total was tuition to cyber charter schools, which is $546 million more than what school districts spent on all student activities such as athletics and extracurriculars.

The cost of charter schools for school districts continue to grow. Since 2007-08, charter school tuition costs have grown by more than $2 billion, or 331% while charter school enrollments have only increased 143%.

As a result, charter school costs are now the most commonly identified source of budget pressure for Pennsylvania school districts. In the 2023 State of Education report, 75% of school districts identified mandatory charter school tuition payments as one of their biggest sources of budget pressure. This was 26% higher than the next highest rated budget pressure.

No.

On its face, it would seem that school districts could reduce their costs when students transfer to charter schools, but that is not the case for several reasons.

First, charter schools not only attract students from school district schools, but also from private schools and home-school programs. This results in school districts absorbing entirely new educational costs.

Second, there are stranded costs that stay with a school district even after a student leaves for a charter school. Imagine a school district elementary school with 50 children in its 3rd grade class at the start of the school year. Those students are divided into two classrooms of 25 each. If five of those students leave the elementary school for a charter school, those students are taking with them as much as $23,000 each (depending on the school district’s tuition rate and assuming none of them are special education students). Where would the school district be able to reduce costs? They can’t. The district would not be able to reduce its teaching staff, building space, maintenance or utility bills. Transportation routes to their buildings would remain unchanged, so the number of drivers, buses and fuel costs remain the same. And, the district would have to maintain enough books and educational supplies for those students in case they decide to return to the district school.

A 2017 study of the financial impact of charter expansion conducted by Research for Action found that the impact of students leaving the district for charter schools, both short term and long term, was consistently negative due to stranded costs. Although the negative financial impact was expected to decrease over time, school districts were never able to recover savings that equaled or surpassed what the district paid in charter school tuition. Even five years after the student leaves, school districts would only be able to recover 44-68% of the costs of charter tuition for each student who left for a charter school.

Third, increased transportation costs. School districts are required to provide transportation services to charter school students even when the charter school is located up to 10 miles outside of a district’s geographic boundaries and on days when the district schools are not in session.

Fourth, charter school authorization costs. School districts, which authorize a brick-and-mortar charter school are responsible for holding public hearings and evaluating charter school applications. In addition, the authorizing school district also monitors the charter school’s performance. Should the authorizing school district attempt to revoke a school’s charter based on performance, that school district would be in for a lengthy and costly legal fight.

No.

Until 2010-11, the state would reimburse school districts for some of their charter school tuition costs. This reimbursement provided roughly $225 million to school districts which was intended to pay up to 30% of a school district’s charter tuition costs. When this reimbursement was eliminated, school districts were left to replace this revenue and increasing tuition costs with local funding – primarily property taxes.This method of funding charter schools is unfair for several reasons which result in inconsistencies and overpayments to charter schools.

First, because the tuition rate calculation is based on the school district’s expenses, it creates significant variations in tuition rates. A charter school could receive vastly different tuition payments from students in different school districts despite providing those students with the same education.

As of July 2023, for the 381 school districts who have charter tuition rates posted with the PDE for the 2022-23 school year, the range of those rates vary as follows:

The chart below shows the 2022-23 or 2021-22 charter school tuition rates for those school districts which had voluntarily submitted rates to PDE as of November 2023. If a school district is not listed in the chart, the district did not have a tuition rate for the 2022-23 or 2021-22 school years published by PDE. Tuition rates for school districts with an asterisk are from the 2021-22 school year.

Scroll to explore the data or select one or more counties to compare data. Hover over a data point for more information. Ctrl and click to add more than one county.

Second, the calculation does not consider what charter schools need to provide an education. This is particularly true for cyber charter schools. Without much of the overhead of traditional school districts and brick-and-mortar charter schools (e.g., buildings, utilities, maintenance, etc.), cyber charter schools benefit from receiving inflated tuition rates.

Third, the calculation includes several school district costs that charter schools do not have (or at least go well beyond those of charter schools) and includes numerous costly mandates that may not apply to charter schools. For example, the calculation includes:

- Charter school tuition costs. Paying tuition to charter schools is an expense that is unique to school districts. Yet, school districts are required to pay charter schools as if they have those same expenses. This flaw is of particular importance because of the cyclical inflationary impact it has. The more a school district spends on charter school tuition, the higher their charter school tuition rate will be the next year, which leads to the district spending more on charter school tuition, which drives their tuition rates up, and so on. In 2021-22, the inclusion of charter school tuition payments in the tuition rate calculation inflated the average school district’s regular education tuition rate by $572 and special education rate by $2,584. Though in school districts with significant charter school populations over time, this impact is significantly higher.

- Contributions to the public school employees’ retirement system (PSERS). The charter school law only requires charter schools to provide their employees with a retirement program. With mandatory employer contributions to PSERS above 30% for the foreseeable future (meaning that participating school entities are required to contribute an additional 30 cents on every dollar spent on salaries to PSERS), having the ability to not participate in PSERS presents the opportunity for considerable savings. In 2021-22, 22 charter schools did not report any contributions to PSERS in their Annual Financial Reports.

- Expenses for gifted education. School districts are required to identify students who are gifted and provide them with an individualized educational program, charter schools are not.

- Expenses for career and technical education. State regulations, which also do not apply to charter schools, require school districts to make career and technical education available to any student in the school district’s high school.

- Costs to provide health services to nonpublic schools. State law and regulations require school districts to provide school nurse services to private and parochial schools within its jurisdiction.

- Tax collection costs. In order to generate the local revenues vital to school district operations, district leaders are required to incur the costs associated with levying, assessing and collecting taxes. However, charter schools, as non-taxing authorities, would not have any of these costs.

School districts also provide a variety of extracurricular and non-instructional programs for students that go well beyond those offered or provided by charter schools. This includes interscholastic athletics, clubs, band, theater, and other activities. Charter schools may also provide these activities, but school districts are required to allow charter school students to participate in school district activities in most instances. It also includes food services, library services, and health services which cyber charter schools do not provide.

And as those costs have increased, so too have school district tuition rates. Compared to 2007-08, the average charter school tuition rate has increased 98% for special education and 66% for regular education with most of those increases coming since the 2012-13 school year.

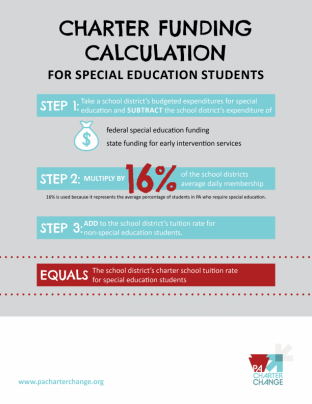

Finally, the calculation makes several assumptions about special education students that result in school district overpayments. Specifically, the calculation assumes that 16% of all students will need special education programs and services and then it assumes that all special education students will need programs and services costing the same amount. For more information on how this happens and its impact, see “School districts are overpaying charter schools for special education” below.

In 2021-22, roughly 313,000, or 18.6% of students in Pennsylvania public schools were identified as needing special education. However, charter schools identified a higher percentage of students for special education.

Although charter schools enroll/identify a higher percentage of special education students, school districts are responsible for most students requiring the most intensive and costly services.

In 2020-21, which is the latest year for which data are available from PDE, more than 93% of the students requiring the most extensive special education services, those costing more than $26,718 per student, were educated by or through a school district.

In comparison, more than 93% of all charter school special education students were educated for less than $26,718. Yet, because the tuition calculation is based on the school district’s expenses, the average charter school special education tuition rate paid to charters by districts was $28,500.

A 2016 PSBA study of PDE charter school enrollment data found that school districts paid charter schools more than $100 million more for special education than charter schools reported spending on special education. By the 2020-21 school year, that overpayment had grown to $185 million. It should be noted that under the charter school law, charter schools are not obligated to use these special education revenues for special education purposes and there is no mechanism for school districts to seek repayment of unused funds.

The special education funding formula for school districts correctly recognizes that not all students identified for special education have the same educational needs and costs. The formula considers the number of low, moderate and high-need students in the school district and includes factors related to school district wealth, property tax levels, and rural and small district conditions.

The goal was to create a more accurate funding system where special education resources were targeted to schools with the highest special education costs and address concerns with the potential incentive for over-identification of students needing special education.

This formula was developed by the Pennsylvania Special Education Funding Commission following an extensive study, conducted with input from education stakeholders, including school districts and charter school entities.

Although the new special education funding formula was intended to apply equally to school districts and charter schools, the law as it was passed affects only school districts. No changes were made to apply the funding formula to charter schools because of the opposition from charter school groups.

Yes.

The current funding method allows charter schools to frequently receive more money than needed to educate a special education student because it provides charter schools with the same funding for each student with a disability, regardless of the severity of that student’s disability.

This has the potential to create a financial incentive for charter schools to identify more students with disabilities that require low-cost services, such as specific learning disabilities and speech/language impairments, but receive reimbursement for high-cost services. It may also create a disincentive for charters to serve students with more severe disabilities because their needs will be more expensive. As noted by the Pennsylvania Auditor General, using a one-size-fits-all approach to special education funding, “makes it tempting to focus more on dollars and less on a student’s need.”

Data indicates that this may be the case. More than 93% of the students requiring the most extensive special education services are educated by or through a school district (see “school districts are overpaying charter schools for special education” above).

Of the special education students enrolled in a charter school in 2017-18, nearly half (47.3%) were identified as having a specific learning disability. In a study funded by the U.S. Department of Education, the Center for Special Education Finance found that per student expenditures were lowest for students with specific learning disabilities and speech/language impairments.

Further, charter schools can currently re-classify a student as needing special education regardless of whether the student was previously classified as such by their home school district, and without review by the authorizing school district that is required to pay increased tuition rates.

Yes, and rightfully so.

In the 2021-22 school year, the revenue per student received by charter schools was only 6.1% less than that of school districts.

The tuition payments received by charter schools, which make more than 80% of charter school funding, are based on a school district’s expenses. Yet school districts have numerous expenses that charter schools do not have (or at least go well beyond those of charter schools) and are subject to costly mandates that charter schools are not. For example, school districts are required to:

- Pay tuition to charter school. Paying tuition to charter schools is an expense that is unique to school districts. Yet, school districts are required to pay charter schools as if they have those same expenses. Tuition payments alone account for more than $2.6 billion (7.6%) of school district spending in 2021-22.

- Provide transportation to charter school students. Even if a school district does not provide transportation to its own students, it is still require to provide transportation to students attending a charter school within the district and charter schools within 10 miles of school district boundaries.

- Participate in the public school employees’ retirement system (PSERS). The charter school law only requires charter schools to provide their employees with a retirement program. With mandatory employer contributions to PSERS above 30% for the foreseeable future (meaning that participating school entities are required to contribute an additional 30 cents on every dollar spent on salaries to PSERS), having the ability to not participate in PSERS presents the opportunity for considerable savings. In 2021-22, 22 charter schools did not report any contributions to PSERS in their Annual Financial Reports.

- Develop special education plans and comply with special education caseload limits. State regulations require school districts to develop and implement a special education plan which specifies the special education programs and services available in the district and impose limits on the number of students that a district special education teacher may have assigned to them. These requirements do not apply to charter schools.

- Identify students who are gifted and provide them with an individualized educational program. State regulations for gifted students, which do not apply to charter schools, require school districts to develop plans to identify, screen, and provide specially designed instruction to children who are gifted.

- Provide students with access to career and technical education programming. State regulations, which also do not apply to charter schools, require school districts to make career and technical education available to any student in the school district’s high school.

- Ensure that every professional staff member is appropriately certified. Charter schools are only required to ensure that at least 75% of their professional staff are appropriately certified. Employing certified educators comes with additional cost to the school entity reflecting the educator’s qualifications.

- Provide health services to nonpublic schools. State law and regulations require school districts to provide school nurse services to private and parochial schools within its jurisdiction.

- Levy, assess and collect local taxes.

- In order to generate the local revenues vital to school district operations, districts are required to incur the costs associated with levying, assessing and collecting taxes.

School districts also provide a variety of extracurricular and non-instructional programs for students that go well beyond those offered or provided by charter schools. This includes interscholastic athletics, clubs, band, theater, and other activities. Charter schools may also provide these activities, but school districts are required to allow charter school students to participate in school district activities in most instances. It also includes food, library and health services which cyber charter schools do not provide.

For a more detailed explanations of the differences in funding between school districts and charter schools, see PSBA’s Closer Look exploring this issue.

Yes, and most do.

School districts across the state are responding to the need to provide high-quality flexible and personalized options as a choice for students and families. According to the 2020 State of Education report, nearly 90% of school districts provide their students a local cyber education program comparable to a cyber charter school. Those cyber programs can be administered directly by the school district or through an intermediate unit.Yes.

The 2020 State of Education report also found that more than 98% of school districts providing a cyber education program were able to provide their programs for “significantly less” or “less” than the school district’s established charter school tuition rate.School district cyber programs:

- Are better at providing special education services for children at all levels of need.

- Provide personalized learning with flexible scheduling that can be parallel with the instruction and opportunities provided to their other students. For example, if students want to participate in specific classes a district does not offer online, then they can go into the school and take those classes.

- Allow students who choose the district’s cyber program to remain part of the school community. Students can easily participate in extracurricular activities the district offers, such as clubs, athletics, fine arts, fairs or attend field trips, speakers, and prom.

- Allow students choosing district cyber programs to easily transition back to regular school district classes and programs.

- Grants students who use a district cyber program a district diploma, and they can walk with their graduating class.